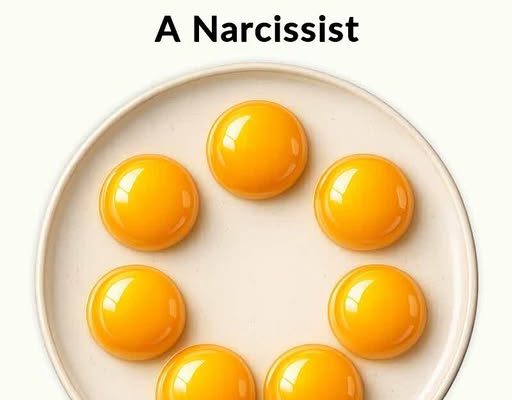

At first glance, images like the “circle-counting” illusion seem harmless, playful, and even a little silly—just another quick distraction in the endless stream of online content. A plate, several egg yolks, a bold headline promising to reveal something profound about your personality, and a simple instruction: count how many circles you see. Most people instinctively comply. They pause, lean closer to the screen, and begin counting. In that moment, something subtle happens. The mind shifts from passive scrolling to active interpretation. Attention sharpens. Curiosity awakens. And suddenly, what looked like a trivial image becomes a small psychological experiment. Some people see only the obvious shapes. Others notice the plate, the empty space, the reflections, the shadows, and even imagined boundaries. When people compare answers, they are often surprised by how different those answers are. This variation creates the illusion that the image must be revealing something deep and personal. Add a provocative label like “narcissist test,” and the effect becomes even stronger. The image stops being entertainment and becomes a mirror—one that seems to reflect hidden truths about how we think, perceive, and judge ourselves. Yet behind this apparent simplicity lies a complex interaction between perception, attention, expectation, and human psychology.

When someone looks at such an image and counts only the seven egg yolks, they are responding to the most direct and concrete visual information available. These viewers tend to focus on what stands out clearly and requires the least interpretation. In daily life, this style of perception often translates into practicality and efficiency. People who favor obvious elements are usually comfortable with clear rules, defined goals, and tangible outcomes. They prefer to work with what is visible and measurable rather than speculate about possibilities or hidden meanings. This does not mean they lack imagination or depth. Instead, it suggests that their minds prioritize clarity and reliability. They conserve mental energy by not overanalyzing every situation. In a world filled with ambiguity, this can be a powerful strength. However, online personality tests often mislabel this trait as “simple” or “unreflective,” which is misleading. Focusing on concrete reality is not a sign of intellectual limitation; it is a cognitive strategy. The human brain constantly decides what to emphasize and what to ignore. Those who see only the yolks are not missing anything—they are choosing efficiency over elaboration. Their perception reflects how they navigate life: grounded, direct, and oriented toward what is immediately relevant.

People who notice eight or nine circles, including the plate and the central empty space, demonstrate a different way of engaging with visual information. These individuals naturally expand their focus beyond the main subject. They look for context, relationships, and structure. When they see the plate, they are recognizing that objects rarely exist in isolation. When they notice the invisible circle formed by empty space, they are responding to negative space—an advanced perceptual skill that artists, designers, and architects often develop. This ability reflects a tendency to think in systems rather than fragments. Such people often ask, “How does this fit into the bigger picture?” rather than “What is right in front of me?” In everyday life, this mindset supports empathy, strategic thinking, and emotional awareness. These individuals may be more sensitive to unspoken tensions, underlying motivations, and subtle patterns in social interactions. Again, online tests sometimes frame this as “deep” or “intuitive,” but it is simply another cognitive orientation. It shows how the mind organizes information. Some brains scan broadly, integrating many elements into a single mental map. Others narrow in on key details. Neither approach is superior. They are complementary ways of understanding reality, shaped by personality, experience, and even momentary mood.

Those who see ten or more circles—counting reflections, highlights, outlines, shadows, and implied shapes—represent yet another cognitive style. These viewers engage in highly detailed, analytical processing. They dissect what they see into components, layers, and possibilities. Their minds are comfortable with complexity and ambiguity. They often question first impressions and enjoy constructing their own interpretations. In problem-solving, this can be a tremendous asset. Such individuals may excel in research, engineering, art, psychology, or any field that rewards careful observation and independent thinking. However, this tendency can also come with challenges. Over-analysis can lead to indecision, mental fatigue, and self-doubt. When every detail feels important, prioritizing becomes difficult. Online tests sometimes label this style as “narcissistic” because of strong confidence in personal perception, but this is a misunderstanding. Trusting one’s interpretation is not narcissism. It is a natural outcome of deep cognitive engagement. Narcissism is a complex personality trait involving entitlement, lack of empathy, and excessive self-focus. It cannot be diagnosed by counting shapes in a picture. What these viewers actually display is intellectual curiosity and a willingness to explore beyond surface-level explanations.

On the other end of the spectrum are those who see fewer than seven circles or do not engage with the task seriously. They may glance briefly and move on, uninterested in analyzing the image. This response is often interpreted negatively in online quizzes, described as distraction or lack of attention. In reality, it frequently reflects something much more ordinary: mental overload, emotional fatigue, or simple prioritization. Modern life demands constant cognitive effort—work, family, social media, news, responsibilities. Not every person has the energy to invest in every small stimulus they encounter. Skipping a visual puzzle does not indicate laziness or shallowness. It indicates that the brain is conserving resources. In psychological terms, attention is a limited currency. We spend it where we believe it matters most. Someone who ignores such an image may be deeply thoughtful in other areas of life but unwilling to invest energy in trivial challenges. This selective engagement is, in many ways, a sign of self-regulation. It shows an awareness—conscious or unconscious—of where one’s mental energy is best used.

The real significance of these images lies not in what they claim to measure, but in how people react to them. Humans are natural meaning-makers. We are drawn to tools that promise insight into who we are. Personality tests, horoscopes, quizzes, and optical illusions all tap into this desire. They offer a shortcut to self-understanding in a world where identity is often complex and uncertain. When an image suggests it can reveal narcissism, intelligence, empathy, or creativity, people feel compelled to participate. This phenomenon is reinforced by social comparison. We want to know how we measure up to others. Did we see what they saw? Did we miss something? Are we “normal”? These questions are deeply human. They reflect our social nature and our need for belonging. Yet most viral tests are designed for entertainment, not diagnosis. They rely on vague interpretations that can apply to almost anyone. Psychologists call this the Barnum effect: people accept general statements as personally meaningful. “You are intuitive.” “You value clarity.” “You trust your perception.” Almost everyone can see themselves in these descriptions. The test feels accurate because it is flexible, not because it is precise.

Ultimately, the number of circles someone sees reveals far less about their personality than the fact that they stopped to count them at all. That pause—the moment of curiosity, reflection, and self-questioning—is the most telling element. It shows a willingness to look inward, to ask what perception says about identity, and to engage with ideas beyond immediate necessity. In a fast-moving digital environment, taking even a few seconds to reflect is meaningful. It suggests openness, awareness, and interest in understanding oneself. True psychological insight does not come from viral images. It comes from long-term self-observation, honest feedback, emotional awareness, and meaningful relationships. Optical illusions can be fun prompts for reflection, but they are not mirrors of the soul. The real value lies in how they remind us that perception is subjective, that reality is filtered through individual minds, and that no two people see the world in exactly the same way. In recognizing this, we gain something far more important than a label: a deeper respect for human diversity, complexity, and the quiet mystery of how each person experiences life.